Learning Rate Schedules

Setting the learning rate for stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is crucially important when training neural networks because it controls both the speed of convergence and the ultimate performance of the network. One of the simplest learning rate strategies is to have a fixed learning rate throughout the training process. Choosing a small learning rate allows the optimizer find good solutions, but this comes at the expense of limiting the initial speed of convergence. Changing the learning rate over time can overcome this tradeoff.

Schedules define how the learning rate changes over time and are typically specified for each epoch or iteration (i.e. batch) of training. Schedules differ from adaptive methods (such as AdaDelta and Adam) because they:

- change the global learning rate for the optimizer, rather than parameter-wise learning rates

- don't take feedback from the training process and are specified beforehand

In this tutorial, we visualize the schedules defined in mx.lr_scheduler, show how to implement custom schedules and see an example of using a schedule while training models. Since schedules are passed to mx.optimizer.Optimizer classes, these methods work with both Module and Gluon APIs.

%matplotlib inline from __future__ import print_function import math import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import mxnet as mx from mxnet.gluon import nn from mxnet.gluon.data.vision import transforms import numpy as np

def plot_schedule(schedule_fn, iterations=1500): # Iteration count starting at 1 iterations = [i+1 for i in range(iterations)] lrs = [schedule_fn(i) for i in iterations] plt.scatter(iterations, lrs) plt.xlabel("Iteration") plt.ylabel("Learning Rate") plt.show()

Schedules

In this section, we take a look at the schedules in mx.lr_scheduler. All of these schedules define the learning rate for a given iteration, and it is expected that iterations start at 1 rather than 0. So to find the learning rate for the 100th iteration, you can call schedule(100).

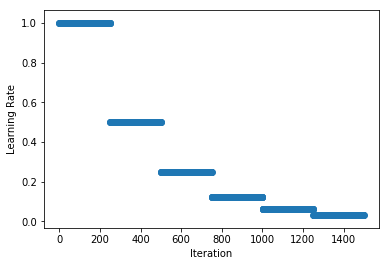

Stepwise Decay Schedule

One of the most commonly used learning rate schedules is called stepwise decay, where the learning rate is reduced by a factor at certain intervals. MXNet implements a FactorScheduler for equally spaced intervals, and MultiFactorScheduler for greater control. We start with an example of halving the learning rate every 250 iterations. More precisely, the learning rate will be multiplied by factor after the step index and multiples thereafter. So in the example below the learning rate of the 250th iteration will be 1 and the 251st iteration will be 0.5.

schedule = mx.lr_scheduler.FactorScheduler(step=250, factor=0.5) schedule.base_lr = 1 plot_schedule(schedule)

Note: the base_lr is used to determine the initial learning rate. It takes a default value of 0.01 since we inherit from mx.lr_scheduler.LRScheduler, but it can be set as a property of the schedule. We will see later in this tutorial that base_lr is set automatically when providing the lr_schedule to Optimizer. Also be aware that the schedules in mx.lr_scheduler have state (i.e. counters, etc) so calling the schedule out of order may give unexpected results.

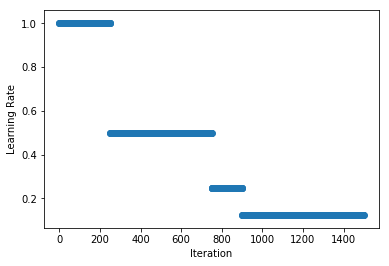

We can define non-uniform intervals with MultiFactorScheduler and in the example below we halve the learning rate after the 250th, 750th (i.e. a step length of 500 iterations) and 900th (a step length of 150 iterations). As before, the learning rate of the 250th iteration will be 1 and the 251th iteration will be 0.5.

schedule = mx.lr_scheduler.MultiFactorScheduler(step=[250, 750, 900], factor=0.5) schedule.base_lr = 1 plot_schedule(schedule)

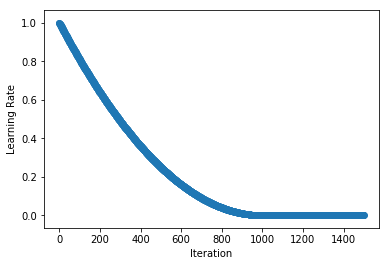

Polynomial Schedule

Stepwise schedules and the discontinuities they introduce may sometimes lead to instability in the optimization, so in some cases smoother schedules are preferred. PolyScheduler gives a smooth decay using a polynomial function and reaches a learning rate of 0 after max_update iterations. In the example below, we have a quadratic function (pwr=2) that falls from 0.998 at iteration 1 to 0 at iteration 1000. After this the learning rate stays at 0, so nothing will be learnt from max_update iterations onwards.

schedule = mx.lr_scheduler.PolyScheduler(max_update=1000, base_lr=1, pwr=2) plot_schedule(schedule)

Note: unlike FactorScheduler, the base_lr is set as an argument when instantiating the schedule.

And we don't evaluate at iteration=0 (to get base_lr) since we are working with schedules starting at iteration=1.

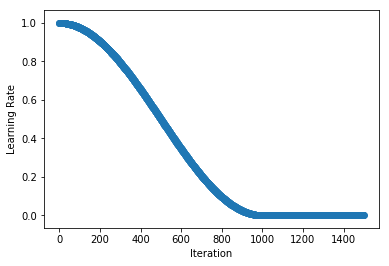

Custom Schedules

You can implement your own custom schedule with a function or callable class, that takes an integer denoting the iteration index (starting at 1) and returns a float representing the learning rate to be used for that iteration. We implement the Cosine Annealing Schedule in the example below as a callable class (see __call__ method).

class CosineAnnealingSchedule(): def __init__(self, min_lr, max_lr, cycle_length): self.min_lr = min_lr self.max_lr = max_lr self.cycle_length = cycle_length def __call__(self, iteration): if iteration <= self.cycle_length: unit_cycle = (1 + math.cos(iteration * math.pi / self.cycle_length)) / 2 adjusted_cycle = (unit_cycle * (self.max_lr - self.min_lr)) + self.min_lr return adjusted_cycle else: return self.min_lr schedule = CosineAnnealingSchedule(min_lr=0, max_lr=1, cycle_length=1000) plot_schedule(schedule)

Using Schedules

While training a simple handwritten digit classifier on the MNIST dataset, we take a look at how to use a learning rate schedule during training. Our demonstration model is a basic convolutional neural network. We start by preparing our DataLoader and defining the network.

As discussed above, the schedule should return a learning rate given an (1-based) iteration index.

# Use GPU if one exists, else use CPU ctx = mx.gpu() if mx.test_utils.list_gpus() else mx.cpu() # MNIST images are 28x28. Total pixels in input layer is 28x28 = 784 num_inputs = 784 # Clasify the images into one of the 10 digits num_outputs = 10 # 64 images in a batch batch_size = 64 # Load the training data train_dataset = mx.gluon.data.vision.MNIST(train=True).transform_first(transforms.ToTensor()) train_dataloader = mx.gluon.data.DataLoader(train_dataset, batch_size, shuffle=True) # Build a simple convolutional network def build_cnn(): net = nn.HybridSequential() with net.name_scope(): # First convolution net.add(nn.Conv2D(channels=10, kernel_size=5, activation='relu')) net.add(nn.MaxPool2D(pool_size=2, strides=2)) # Second convolution net.add(nn.Conv2D(channels=20, kernel_size=5, activation='relu')) net.add(nn.MaxPool2D(pool_size=2, strides=2)) # Flatten the output before the fully connected layers net.add(nn.Flatten()) # First fully connected layers with 512 neurons net.add(nn.Dense(512, activation="relu")) # Second fully connected layer with as many neurons as the number of classes net.add(nn.Dense(num_outputs)) return net net = build_cnn()

We then initialize our network (technically deferred until we pass the first batch) and define the loss.

# Initialize the parameters with Xavier initializer net.collect_params().initialize(mx.init.Xavier(), ctx=ctx) # Use cross entropy loss softmax_cross_entropy = mx.gluon.loss.SoftmaxCrossEntropyLoss()

We‘re now ready to create our schedule, and in this example we opt for a stepwise decay schedule using MultiFactorScheduler. Since we’re only training a demonstration model for a limited number of epochs (10 in total) we will exaggerate the schedule and drop the learning rate by 90% after the 4th, 7th and 9th epochs. We call these steps, and the drop occurs after the step index. Schedules are defined for iterations (i.e. training batches), so we must represent our steps in iterations too.

steps_epochs = [4, 7, 9] # assuming we keep partial batches, see `last_batch` parameter of DataLoader iterations_per_epoch = math.ceil(len(train_dataset) / batch_size) # iterations just before starts of epochs (iterations are 1-indexed) steps_iterations = [s*iterations_per_epoch for s in steps_epochs] print("Learning rate drops after iterations: {}".format(steps_iterations))

Learning rate drops after iterations: [3752, 6566, 8442]

schedule = mx.lr_scheduler.MultiFactorScheduler(step=steps_iterations, factor=0.1)

We create our Optimizer and pass the schedule via the lr_scheduler parameter. In this example we're using Stochastic Gradient Descent.

sgd_optimizer = mx.optimizer.SGD(learning_rate=0.03, lr_scheduler=schedule)

And we use this optimizer (with schedule) in our Trainer and train for 10 epochs. Alternatively, we could have set the optimizer to the string sgd, and pass a dictionary of the optimizer parameters directly to the trainer using optimizer_params.

trainer = mx.gluon.Trainer(params=net.collect_params(), optimizer=sgd_optimizer)

num_epochs = 10 # epoch and batch counts starting at 1 for epoch in range(1, num_epochs+1): # Iterate through the images and labels in the training data for batch_num, (data, label) in enumerate(train_dataloader, start=1): # get the images and labels data = data.as_in_context(ctx) label = label.as_in_context(ctx) # Ask autograd to record the forward pass with mx.autograd.record(): # Run the forward pass output = net(data) # Compute the loss loss = softmax_cross_entropy(output, label) # Compute gradients loss.backward() # Update parameters trainer.step(data.shape[0]) # Show loss and learning rate after first iteration of epoch if batch_num == 1: curr_loss = mx.nd.mean(loss).asscalar() curr_lr = trainer.learning_rate print("Epoch: %d; Batch %d; Loss %f; LR %f" % (epoch, batch_num, curr_loss, curr_lr))

Epoch: 1; Batch 1; Loss 2.304071; LR 0.030000

Epoch: 2; Batch 1; Loss 0.059640; LR 0.030000

Epoch: 3; Batch 1; Loss 0.072601; LR 0.030000

Epoch: 4; Batch 1; Loss 0.042228; LR 0.030000

Epoch: 5; Batch 1; Loss 0.025745; LR 0.003000

Epoch: 6; Batch 1; Loss 0.027391; LR 0.003000

Epoch: 7; Batch 1; Loss 0.048237; LR 0.003000

Epoch: 8; Batch 1; Loss 0.024213; LR 0.000300

Epoch: 9; Batch 1; Loss 0.008892; LR 0.000300

Epoch: 10; Batch 1; Loss 0.006875; LR 0.000030

We see that the learning rate starts at 0.03, and falls to 0.00003 by the end of training as per the schedule we defined.

Manually setting the learning rate: Gluon API only

When using the method above you don‘t need to manually keep track of iteration count and set the learning rate, so this is the recommended approach for most cases. Sometimes you might want more fine-grained control over setting the learning rate though, so Gluon’s Trainer provides the set_learning_rate method for this.

We replicate the example above, but now keep track of the iteration_idx, call the schedule and set the learning rate appropriately using set_learning_rate. We also use schedule.base_lr to set the initial learning rate for the schedule since we are calling the schedule directly and not using it as part of the Optimizer.

net = build_cnn() net.collect_params().initialize(mx.init.Xavier(), ctx=ctx) schedule = mx.lr_scheduler.MultiFactorScheduler(step=steps_iterations, factor=0.1) schedule.base_lr = 0.03 sgd_optimizer = mx.optimizer.SGD() trainer = mx.gluon.Trainer(params=net.collect_params(), optimizer=sgd_optimizer) iteration_idx = 1 num_epochs = 10 # epoch and batch counts starting at 1 for epoch in range(1, num_epochs + 1): # Iterate through the images and labels in the training data for batch_num, (data, label) in enumerate(train_dataloader, start=1): # get the images and labels data = data.as_in_context(ctx) label = label.as_in_context(ctx) # Ask autograd to record the forward pass with mx.autograd.record(): # Run the forward pass output = net(data) # Compute the loss loss = softmax_cross_entropy(output, label) # Compute gradients loss.backward() # Update the learning rate lr = schedule(iteration_idx) trainer.set_learning_rate(lr) # Update parameters trainer.step(data.shape[0]) # Show loss and learning rate after first iteration of epoch if batch_num == 1: curr_loss = mx.nd.mean(loss).asscalar() curr_lr = trainer.learning_rate print("Epoch: %d; Batch %d; Loss %f; LR %f" % (epoch, batch_num, curr_loss, curr_lr)) iteration_idx += 1

Epoch: 1; Batch 1; Loss 2.334119; LR 0.030000

Epoch: 2; Batch 1; Loss 0.178930; LR 0.030000

Epoch: 3; Batch 1; Loss 0.142640; LR 0.030000

Epoch: 4; Batch 1; Loss 0.041116; LR 0.030000

Epoch: 5; Batch 1; Loss 0.051049; LR 0.003000

Epoch: 6; Batch 1; Loss 0.027170; LR 0.003000

Epoch: 7; Batch 1; Loss 0.083776; LR 0.003000

Epoch: 8; Batch 1; Loss 0.082553; LR 0.000300

Epoch: 9; Batch 1; Loss 0.027984; LR 0.000300

Epoch: 10; Batch 1; Loss 0.030896; LR 0.000030

Once again, we see the learning rate start at 0.03, and fall to 0.00003 by the end of training as per the schedule we defined.

Advanced Schedules

We have a related tutorial on Advanced Learning Rate Schedules that shows reference implementations of schedules that give state-of-the-art results. We look at cyclical schedules applied to a variety of cycle shapes, and many other techniques such as warm-up and cool-down.